Link Prediction

|

Important - page not maintained

This page is no longer being maintained and its content may be out of date. For the latest guidance, please visit the Neo4j Graph Data Science Library . |

In this guide, we will learn about concepts related to link prediction, which is used to predict missing or future links in graphs.

Intermediate

What is link prediction?

Link prediction has been around for a long time, but was popularised by a paper written by Jon Kleinberg and David Liben-Nowell in 2004, titled The Link Prediction Problem for Social Networks.

Kleinberg and Liben-Nowell approach this problem from the perspective of social networks, asking the question:

Given a snapshot of a social network, can we infer which new interactions among its members are likely to occur in the near future? We formalize this question as the link prediction problem, and develop approaches to link prediction based on measures for analyzing the “proximity” of nodes in a network.

More recently, Dr Jim Webber, Chief Scientist at Neo4j, explains how the evolution of a graph can be determined from its structure in his entertaining GraphConnect San Francisco 2015 talk where he explained World War 2 using graphs.

Use Cases

Apart from predicting World Wars or friendships in a social network where else might we want to predict links?

We could predict future associations between people in a terrorist network, associations between molecules in a biology network, potential co-authorships in a citation network, interest in an artist or artwork, to name just a few use cases.

In each these examples, predicting a link means that we are predicting some future behaviour. For example in a citation network, we’re actually predicting the action of two people collaborating on a paper.

Link Prediction algorithms

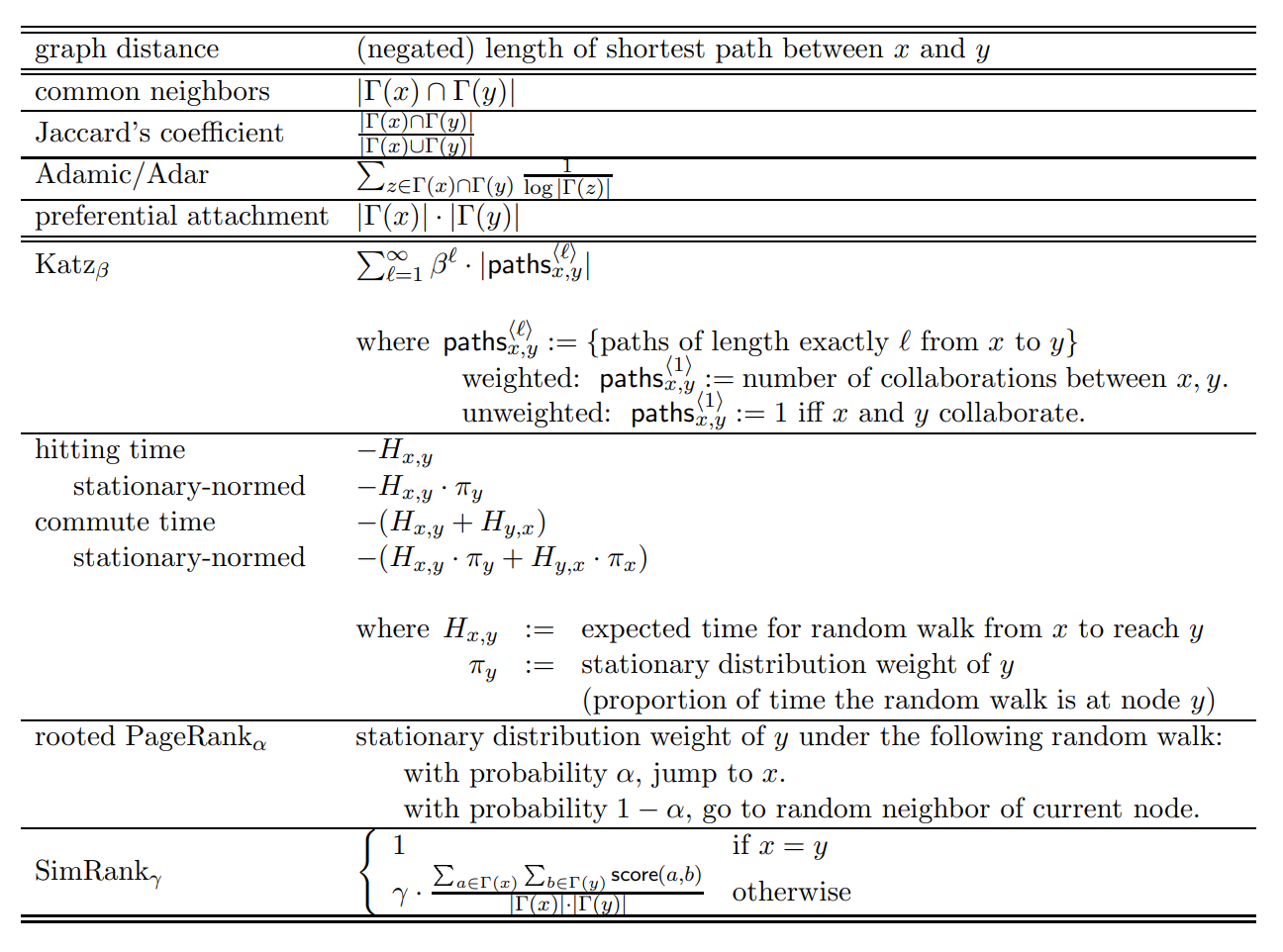

Kleinberg and Liben-Nowell describe a set of methods that can be used for link prediction. These methods compute a score for a pair of nodes, where the score could be considered a measure of proximity or “similarity” between those nodes based on the graph topology. The closer two nodes are, the more likely there will be a relationship between them.

A list of the methods described in the paper are shown below:

The Neo4j Data Science Library supports some of the distance metrics described in the paper, as well as other measures of node proximity.

Link Prediction approaches

While we can use the link prediction algorithms to compute node proximity scores, we need to do something with those scores to predict links. There are two approaches described in the literature:

- Use the measures directly

-

We can use the scores from the link prediction algorithms directly. With this approach we would set a threshold value above which we would predict that a pair of nodes will have a link. In the example above we might say that every pair of nodes that has a preferential attachment score above 3 would have a link, and any with 3 or less would not.

- Supervised learning

-

We can take a supervised learning approach where we use the scores as features to train a binary classifier. The binary classifier then predicts whether a pair of nodes will have a link.

Guillaume Le Floch describes these two approaches in more detail in his blog post Link Prediction In Large-Scale Networks.

Selecting a machine learning model

If we’re using the supervised learning approach, one of the first things we need to do is decide which machine learning model we’re going to use.

Many of the link prediction measures that we’ve covered so far are computed using similar data, and when it comes to training a machine learning model this means there is a feature interaction issue that we need to deal with. Some machine learning models assume that the features they received are independent. Providing such a model with features that don’t meet this assumption will lead us to predicts things with low accuracy. If we choose one of these models we would need to exclude features with high interaction.

Alternately, we can choose a model where feature interaction isn’t so problematic. Ensemble methods tend to work well as they don’t make this assumption on their input data. This could be a gradient boosting classifier as described in Guillaume Le Floch’s blog post or a random forest classifier as described in a paper written by Kyle Julian and Wayne Lu.

Train and test data sets

We also need to decide how we’re going to split our train and test datasets. We can’t randomly split the data, using a built-in function from our machine learning library of choice, as this could lead to data leakage.

Data leakage can occur when data outside of your training data is inadvertently used to create your model. This can easily happen when working with graphs because pairs of nodes in our training set may be connected to those in the test set.

When we compute link prediction measures over that training set the measures computed contain information from the test set that we’ll later evaluate our model against.

Instead we need to split our graph into training and test sub graphs. If our graph has a concept of time our life is easy — we can split the graph at a point in time and the training set will be from before the time, the test set after.

This is still not a perfect solution and we’ll need to try and ensure that the general network structure in the training and test sub graphs is similar.

Once we’ve done that we’ll have pairs of nodes in our train and test set that have relationships between them. They will be the positive examples in our machine learning model.

Now for the negative examples. The simplest approach would be to use all pair of nodes that don’t have a relationship. The problem with this approach is that there are significantly more examples of pairs of nodes that don’t have a relationship than there are pairs of nodes that do. The maximum number of negative examples is equal to:

|

# negative examples = (# nodes)² - (# relationships) - (# nodes) |

i.e. the number of nodes squared, minus the relationships that the graph has, minus self relationships.

If we use all of these negative examples in our training set we will have a massive class imbalance — there are many negative examples and relatively few positive ones.

A model trained using data that’s this imbalanced will achieve very high accuracy by predicting that any pair of nodes don’t have a relationship between them, which is not quite what we want!

So we need to try and reduce the number of negative examples. An approach described in several link prediction papers is to use pairs of nodes that are a specific number of hops away from each other.

This will significantly reduce the number of negative examples, although there will still be a lot more negative examples than positive.

To solve this problem we either need to down sample the negative examples or up sample the positive examples.